[ad_1]

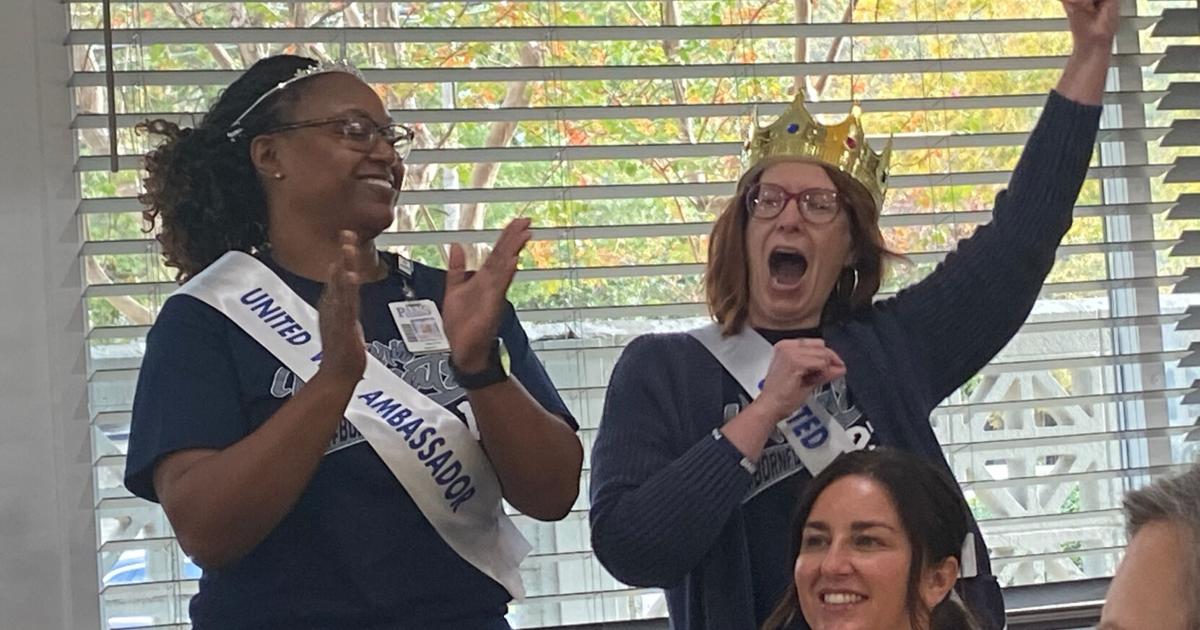

Inform not deform: {Le Journal du Dimanche} staff protest against the nomination of Geoffroy Lejeune as the paper’s new editor, Paris, 19 July 2023

Bertrand Guay · AFP · Getty

Just over a year ago, on 19 October 2022, European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen solemnly told the EU parliament, ‘Targeted attacks on civilian infrastructure with the clear aim to cut off men, women, children [from] water, electricity and heating with the winter coming, these are acts of pure terror and we have to call it as such.’

This rule no longer applies, though, when the ‘targeted attacks’ are committed by an ally of the Western bloc. Following the massacre of hundreds of Israeli civilians during the military operation led by Hamas on 7 October (1,400 dead, including 300 soldiers), defence minister Yoav Galant announced a complete siege of Gaza on 9 October: ‘There will be no electricity, no food, no fuel … We are fighting human animals and we are acting accordingly.’

Within two days, 1,200 bodies had been pulled from the rubble of homes, schools, hospitals and media organisations in Gaza indiscriminately bombed on the pretext – the same one put forward by the Russian army in a different conflict – that they harboured fighters. Undaunted, Von der Leyen reaffirmed, ‘Europe supports Israel.’ In France, the National Assembly’s president Yaël Braun-Pivet declared its ‘unconditional support’ for Israel.

The French media’s focus on war crimes committed by Hamas fighters has reframed the whole Israeli-Palestinian conflict as being about Islamist terrorism. Once this reframing has occurred in a country scarred by multiple Islamist attacks, the media’s role ceases to be providing information and becomes about relaying the authorities’ tough new orders and pursuing those who challenge them.

The week after Hamas’s attack, the French government further assailed fundamental freedoms – already eroded under Covid lockdowns – by prohibiting expressions of support for Palestine, without the self-appointed guardians of democracy objecting. This came in a directive from the justice minister to prosecutors on 10 October, outlawing ‘the public dissemination of messages encouraging a favourable assessment of Hamas or Islamic Jihad’, even if such statements were ‘made in the context of a public interest debate and could claim to be part of political discourse’.

The media elite immediately launched their own ‘debate’ – not on freedom of expression (though they claim to champion it), but about the need to prosecute or disband political groups that justify or seek to explain Palestinian resistance, which was from its inception categorised as terrorist – though both Charles de Gaulle and Jacques Chirac once disagreed.

Whose fake news slips through?

The bias of editorial boards stems less from insidious intent than genuine blindness. To accuse them of double standards would mean lamenting their deviation from a standard they abandoned long ago: equal treatment for and equal dignity of all human beings. Former public television star presenter David Pujadas encapsulated the mindset of many luminaries in his profession on LCI (11 October): should we consider Gazans as complicit with Hamas as Russians might be with the Kremlin, he wondered or, making a superhuman effort to empathise, ‘should we say “a civilian in Gaza is the same as a civilian in Israel”?’ He would have been puzzled by the answer the BBC’s world affairs editor John Simpson gave when criticised for not calling Hamas a terrorist organisation: ‘Our business is to present our audiences with the facts, and let them make up their own minds’ (1).

French newsrooms, radicalised by the 2015 and 2016 attacks, automatically equate any view that’s critical of policies from Washington, Brussels or Paris with provocation or even illegality. For them, reporting means filtering facts through Atlanticist values. They see the ‘international community’ as a Western brotherhood. The murder of a reporter in Moscow prompts them – rightly – to challenge an authoritarian regime; the killing of ten Palestinian journalists elicits only a sad shrug. As of 14 October, Israel was responsible for the deaths of nearly a third of the journalists killed worldwide in 2023 (2). A thousand articles detail Russian and Hamas disinformation, but Ukrainian or Israeli fake news slips past unchecked.

Our business is to present our audiences with the facts, and let them make up their own minds

John Simpson

There’s another constant in the coverage of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict: the obscuring of history. The issue only makes it into the TV news headlines when a Palestinian attack occurs. Yet ignoring what preceded it – colonisation, expulsions, murders, destruction of wells and crops, humiliations – amounts to systematically presenting Israel as a victim acting in self-defence. ‘Israel is responding, the Israeli government says this is a response,’ insisted journalist Benjamin Duhamel of the bombing of Gaza (BFMTV, 13 October 2023).

Le Monde diplomatique was founded in opposition to this kind of editorial apartheid. From its creation in 1954 until the 1980s, it supported first the decolonisation and then the non-aligned movement, the group of countries that refused to choose between the two blocs and defended their national independence through autonomous development, often under the socialist banner. Back then, it was not alone. It’s troubling in retrospect to think that L’Express, Le Nouvel Observateur and Le Monde were once capable of showing understanding towards the ‘terrorists’ of the Algerian National Liberation Front, who were also responsible for civilian massacres, and covered the campaigns of their defenders.

These three publications have since shifted ‘westward’. And the Global South, which is now asserting itself against the Western bloc, bears little resemblance to the new world that shook off the colonial yoke half a century ago. Having been converted to the free market, fragmented, and having lost a sense of emancipatory potential, it calls for a rebalancing of international forces, but mainly to compete effectively with the North on its own terms.

For a publication like ours, refusing to be carried along in the Western bubble is now more challenging than ever: outside times of crisis, the number of people who are seriously interested in international issues is shrinking. And the oxygen for progressivism becomes thin as the political world increasingly aligns itself with US positions. The rising tide of new information technologies has done nothing to reverse this trend.

Editorial line: a meeting at Le Monde, Paris, 13 March 2023

Joel Saget · AFP · Getty

The all-powerful image

The thumb flicks the phone screen reflexively, endlessly scrolling through video clips – first those related to your search, then others selected by the algorithm and then still others with no link to the original subject. As the images flash by, your mind disengages and goes numb. Yet an uncontrollable desire to view glues you to the screen. Digital industries would like to turn consumers of news into a zombie army stumbling between photos of cats and scenes of massacres. Almost unnoticed, they have effected a profound transformation in the ways we access knowledge: narrowing the field of reading and expanding that of the image.

To Silicon Valley investors reading is not just obsolete, it’s dangerous: time-consuming, attention- and concentration-sapping, it’s an expression of self-determination over how, what and when we read. ‘Why read?’ these new monetisers of our brain space ask. ‘Just look at the pictures instead.’

With Google’s acquisition of YouTube in 2006 and the rise of social media, raw (and often brutal) video clips have become the dominant form of news. Such clips, filmed by a protagonist or eyewitness on a phone, drone or surveillance camera, and detached from all context, stimulate emotions – positive and negative – and the compulsion to react without thinking. Going viral means profit. ISIS’s carefully staged attacks and massacres in 2015-16 normalised these videos: the visual manifestations of obscurantist terror filled the screens of news channels and the feeds designed by Silicon Valley’s software engineers. Short-form videos – ‘reels’, ‘stories’, ‘shorts’, ‘snaps’ – that mash together birthday parties, dance moves, football goals and murder scenes are now front and centre on Instagram, TikTok and platforms that originally focused on the written word, such as X (formerly Twitter).

Under pressure from social media and 24-hour news channels, most major newspapers have added similar formats on their homepages to attract a much younger audience than their generally ageing readership. From the anonymous X user to political leaders, everyone now reacts to images as if they were the event itself: ‘What was your reaction when you first saw the images?’ Libération (13 October) asked the Greens’ national secretary. ‘The images that everyone has seen show the absolute horror of the terrorist attack carried out by Hamas.’

Not giving an immediate reaction to shocking images is now regarded as odd. Or worse: possible proof of a lack of humanity. Thomas Legrand, a journalist at France Inter and Libération, invoked the virtues of ‘impulse politics’ to criticise La France Insoumise for failing to express emotion quickly enough: ‘The true nature of a political movement can be gauged by its first reaction to a dramatic event when it’s still about fundamental principles and there hasn’t been time to weigh every aspect of the issue’ (Libération, 10 October 2023). This is an astonishing turnaround: political leaders have long prided themselves on being able to abstract themselves from events to weigh causes and consequences on the scales of reason.

A unique economic model

Can a newspaper resist the domination of the instant reaction and stop imposing an emotional tone on the news? Given that younger generations are said – sometimes wrongly – to get all their news from social media or influencers, Le Monde diplomatique’s number might appear to be up. Yet, as it approaches its 70th birthday next May, the paper continues to demand from its readers the time, reflection and attention that international news and the battle of ideas require.

Against the prevailing frenzy, it offers historical perspective, reportage from journalists who are specialists, and committed but well-sourced, analysis. Though it does not hide its opinions behind the pretence of objectivity, our publication prides itself on having dissenting readers who, even when they disagree with us, appreciate that, instead of sermonising, we give them fact-checked information they’d struggle to find elsewhere.

This seriousness may admittedly be demanding fare: we publish no video debates, no sofa interviews, no celebrity profiles, no news feeds, no consumer reviews of the best travel pillows. Our website, launched before all our peers in February 1995, is not designed to sell ads or user data, but to offer our articles for reading. And despite this, Le Monde diplomatique carries on: circulation has broadly held up while the industry has been decimated.

Le Monde diplomatique’s unique business model has helped us to determine our path and given us autonomy and independence: in 1996, the newspaper’s readers formed the Association of Friends of Le Monde diplomatique and purchased 25% of its capital; the editorial team, as members of the Gunter Holzmann Association (named after a generous donor whose bequest catalysed the movement) holds a further 24% of the shares. Together, these two blocs have a veto over key business decisions. And crucially, the director is elected every six years by our entire team, not just our journalists.

Ignacio Ramonet and Bernard Cassen, who then headed the newspaper, were bold enough to raise the question of media ownership at a time when the very mention of it caused apoplexy among leader writers. ‘The assertion that being owned by economic interests means you’re not free is baseless,’ Laurent Joffrin said on Canal Plus in June 1999. It was ‘intellectual terrorism’ according to Patrick Poivre d’Arvor or ‘crypto-Le Pen populism’ in the opinion of Franz-Olivier Giesbert – our path was certainly not rose-strewn.

Twenty-five years later, the fact that 90% of the French media belongs to nine billionaires sounds almost like a statement of the obvious to be greeted with a mere roll of the eyes. We played no small part in this awareness. Our diagram of who owns what in the French media has long been one of Le Monde diplomatique’s most viewed publications. Its first iteration, published in 2007, was passed around like samizdat. Back then, publications relied on codes of conduct, shareholder agreements and other theoretical measures to supposedly decouple ownership from control. Vincent Bolloré’s brutal takeover of I-télé in 2016 and the transformation of this hip news channel into a bastion of the far-right renamed CNews, the similar fate suffered by Le Journal du Dimanche, and Elon Musk’s purchase and ideological conversion of Twitter, proved the threat was real.

However, the success of our ownership diagram hides a misunderstanding. What Le Monde diplomatique was proposing was a structural approach: despite being an essential collective service, news is now produced as a low-cost commodity. It should, in fact, be removed from both market and state censorship by socialising it on the model of social security (3).

Many critics of the current media monopoly don’t want to change the game but merely vet who gets to play. Selling newspapers as if they were bags of potatoes is fine by them, as long as the new shareholders behave themselves (4). Bernard Arnault (Le Parisien, Les Échos, Radio Classique): yes. Bolloré (C8, CNews, Europe1, Le Journal du Dimanche): no. So in educated circles the critique of the commodification of news often translates into a political fight against far-right media which, even if successful, would leave the underlying structure unchanged.

The bogeyman of the ‘nine billionaires’, now a cliché, allows us to ignore other significant media aberrations that have nothing to do with shareholder power: the lockstep treatment of certain subjects such as the 2020 lockdown or the war in Ukraine, both in the public sector (France Télévisions, France Inter) and the private (TF1, RTL), in independent publications (Médiapart) and those that are part of an industrial group (Libération and Le Figaro).

The great electronic ocean

The pro-Western radicalisation of newsrooms, information swamped by images and emotion, the rise of clickbait journalism driven by automation, and the attrition of distribution networks are factors that certainly do not play in Le Monde diplomatique’s favour. The influx of subscriptions during lockdown receded two years later; this year, our newsstand sales have been static. In 2023 the total paid circulation of our French edition is expected to drop by about 8% compared to the previous year, settling at just over 160,000 copies a month. Two reasons for this recur in letters we receive: time and money. If the paper sits unread on the coffee table, why buy it? And when inflation is eroding spending power, is a monthly magazine that focuses on the wider world really essential?

Similar difficulties have hit many publications. In August 2023 single-copy sales of French national dailies were down 8.6% compared to the previous year, while weeklies had fallen by 10.4% and monthlies 12.1%. The regional press is suffering too, with numerous layoffs since January, which further weakens a distribution network that went from 28,579 outlets in 2011 to 20,232 in 2022.

Such newsstand closures create a vicious cycle in which sales decline leads to the disappearance of more sales outlets, which in turn reduces the likelihood of readers coming across a publication. Publishers have consequently backed digital and are offering subscriptions at bargain-basement prices that enable subscribers to open links they come across on social media – and the tech giants to harvest data. The aim is no longer to construct an argument organised around a view of the world – an editorial intention – but to cast articles adrift on the vast electronic ocean.

Though touted as the answer, this strategy may fail: several platforms have changed their algorithms to the detriment of journalism, having grown tired of paying press copyright fees and being criticised for widening political divisions (as after the assault on the Capitol in January 2021). So now X promotes controversial influencers and Facebook favours friends-and-family posts over news.

Tests have shown that Facebook has the power to reduce traffic to sites such as the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal by 40-60%. Mother Jones, a leftwing US monthly focused primarily on political and social issues, saw traffic to its Facebook page drop by 75% in 2022 (5). Le Monde diplomatique is not exempt from such manipulation. Although not heavily reliant on social media, its site used to get many new readers from these platforms. Admittedly, dramatic international news still drives readers to our coverage. But lately, this has been more likely to overwhelm than uplift.

Le Monde diplomatique’s circulation remains insufficient to popularise the non-aligned worldview we champion and which runs counter to current French press trends. Our aim to step back and put current events in perspective matches our commitment to present our arguments to the highest standard.

In an era when discourse easily succumbs to trends, ‘hot takes’ and controversies, Le Monde diplomatique aims for consistency. We don’t change our line or abandon certain causes on the grounds that they have been co-opted and distorted by forces we oppose. Marine Le Pen and Éric Zemmour freely criticise the EU and its single currency while praising the virtues of protectionism; Donald Trump and Viktor Orbán denounce some of NATO’s actions; the US alt-right claims to defend freedom of expression against tech giants’ censorship… Instead of abandoning the battle of ideas on the pretext that the ground is contaminated, Le Monde diplomatique stands firm, flag aloft, and exposes the hypocrisy of the new converts: the alt-right defends freedom of expression online (to make racist statements), but bans schoolbooks or progressive publications and removes from the foreign affairs committee a Democratic congresswoman, Ilhan Omar, who dared defend the Palestinians.

Staying means facing stormy seas. ‘Red-brown,’ ‘conspiracy theorist’, ‘journalistic shipwreck’, ‘pro-Russian rag’, ‘enemies of the West’, ‘friends of the terrorist group Hamas’, ‘a newspaper that has always defended crime’: such accusations abound on social media, and are not always only propagated by our declared enemies. Analysing divisions among those who could be united in a common cause or trying to understand political defeats rather than always looking for a future victory can provoke irritation and discouragement among those for whom the will to believe too often outweighs the reasons to doubt. It’s the price of lucidity. After all, what use would a newspaper be if it was designed to flatter its readers’ certainties? As Jean-Paul Sartre once wrote, sometimes ‘we must gauge the obviousness of an idea by the displeasure it causes us.’

Spread the word

Producing an international newspaper such as this is only achievable with your resolute commitment and support. Each time this publication has faced challenging waters, your momentum has kept us going and inspired us. We call upon you again, this time to introduce the Diplo to an audience that’s still unaware of it and to encourage them to subscribe. Mobilise friends, family, colleagues, comrades: this recruitment drive is led jointly by the Association of Friends of Le Monde diplomatique.

If X, Facebook and Instagram adjust their algorithms to the detriment of the press, it matters little to us since our readers constitute our most powerful social network. You may be better able than us to describe this unique publication. You might often be met with the response ‘We don’t have time anymore.’ But even this rare resource, sometimes squandered on rolling news and social media, can be reclaimed. ‘Becoming better informed is tiring,’ Ignacio Ramonet once wrote (6). That’s true, but it’s a prerequisite for enlightened personal judgment and the basis for collective emancipation.

[ad_2]

Source link